Running and Quitting

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

How can I run Python programs?

Objectives

Launch the Jupyter Notebook, create new notebooks, and exit the Notebook.

Create Markdown cells in a notebook.

Create and run Python cells in a notebook.

Python programs are plain text files.

- They have the “.py” extension to let everyone (including the operating system)

know it is a Python program.

- This is convention, not a requirement.

- It’s common to write them using a text editor but we are going to use Jupyter Notebooks in Visual Studio Code.

- The bit of extra setup is well worth it because the Notebook provides code completion and other helpful features.

- Notebook files have the extension “.ipynb” to distinguish them from plain-text Python programs.

Use the Jupyter Notebook for editing and running Python.

- Make sure you have the “Jupyter” plugin installed.

- You can type code into the notebook panel and see the result directly.

- This has several advantages:

- You can easily type, edit, and copy and paste blocks of code.

- Tab complete allows you to easily access the names of things you are using and learn more about them.

- It allows you to annotate your code with links, different sized text, bullets, etc to make it more accessible to you and your collaborators.

- It allows you to display figures next to the code that produces them to tell a complete story of the analysis.

- The notebook is stored as JSON but can be saved as a .py file if you would like to run it from the bash shell or a python interpreter.

How It’s Stored

- The notebook file is stored in a format called JSON.

- Just like a webpage, what’s saved looks different from what you see in your browser.

- But this format allows Jupyter to mix software (in several languages) with documentation and graphics, all in one file.

The Notebook has Control and Edit modes.

- Open a new notebook by hitting CtrlShiftP (or .CmdShiftP on a Mac) and typing “new notebook” to find the “Create: New Jupyter Notebook” option.

- Each notebook contains one or more cells of various types.

Code vs. Text

We often use the term “code” to mean “the source code of software written in a language such as Python”. A “code cell” in a Notebook is a cell that contains software; a “text cell” is one that contains ordinary prose written for human beings.

- If you press “esc” and “return” alternately,

the outer border of your code cell will change from gray to green.

- The difference in color is subtle.

- These are the control (gray) and edit (green) modes of your notebook.

- If you use the “esc” and “return” keys to make the surround gray and then press the “H” key, a list of all the shortcut keys will appear.

- When in control mode (esc/gray),

- The “B” key will make a new cell below the currently selected cell.

- The “A” key will make one above.

- The “X” key will delete the current cell.

- There are lots of shortcuts you can try out and most actions can be done with the menus at the top of the page if you forget the shortcuts.

- If you remember the “esc” and “H” shortcut, you will be able to find out all the rest.

Use the keyboard and mouse to select and edit cells.

- Pressing the “return” key turns the surround green to signify edit mode and you can type into the cell.

- Because we want to be able to write many lines of code in a single cell, pressing the “return” key when the border is green moves the cursor to the next line in the cell just like in a text editor.

- We need some other way to tell the Notebook we want to run what’s in the cell.

- Pressing the “return” key and the “shift” key together will execute the contents of the cell.

- Notice that the “return” and “shift” keys on the right of the keyboard are right next to each other.

The Notebook will turn Markdown into pretty-printed documentation.

- Notebooks can also render Markdown.

- A simple plain-text format for writing lists, links, and other things that might go into a web page.

- Equivalently, a subset of HTML that looks like what you’d send in an old-fashioned email.

- Turn the current cell into a Markdown cell by entering the control mode (esc/gray) and press the “M” key.

In [ ]:will disappear to show it is no longer a code cell and you will be able to write in Markdown.- Turn the current cell into a Code cell by entering the control mode (esc/gray) and press the “Y” key.

Markdown does most of what HTML does.

* Use asterisks

* to create

* bullet lists.

- Use asterisks

- to create

- bullet lists.

1. Use numbers

1. to create

1. numbered lists.

- Use numbers

- to create

- numbered lists.

# A Level-1 Heading

A Level-1 Heading

## A Level-2 Heading (etc.)

A Level-2 Heading (etc.)

Line breaks

don't matter.

But blank lines

create new paragraphs.

Line breaks don’t matter.

But blank lines create new paragraphs.

[Create links](http://software-carpentry.org) with `[...](...)`.

Or use [named links][data_carpentry].

[links]: http://datacarpentry.org

Create links with [...](...).

Or use named links.

Creating Lists in Markdown

Create a nested list in a Markdown cell in a notebook that looks like this:

- Get funding.

- Do work.

- Design experiment.

- Collect data.

- Analyze.

- Write up.

- Publish.

More Math

What is displayed when a Python cell in a notebook that contains several calculations is executed? For example, what happens when this cell is executed?

7 * 3 2 + 1

Change an Existing Cell from Code to Markdown

What happens if you write some Python in a code cell and then you switch it to a Markdown cell? For example, put the following in a code cell:

x = 6 * 7 + 12 print(x)And then run it with shift+return to be sure that it works as a code cell. Now go back to the cell and use escape+M to switch the cell to Markdown and “run” it with shift+return. What happened and how might this be useful?

Mathematics

Standard Markdown (such as we’re using for these notes) won’t render equations, but the Notebook will. Create a new Markdown cell and enter the following:

$\Sigma_{i=1}^{N} 2^{-i} \approx 1$(It’s probably easier to copy and paste.) What does it display? What do you think the underscore

_, circumflex^, and dollar sign$do?

Key Points

Python programs are plain text files.

Use the Jupyter Notebook for editing and running Python.

The Notebook has Control and Edit modes.

Use the keyboard and mouse to select and edit cells.

The Notebook will turn Markdown into pretty-printed documentation.

Markdown does most of what HTML does.

Python Fundamentals

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

What basic data types can I work with in Python?

How can I create a new variable in Python?

Can I change the value associated with a variable after I create it?

Objectives

Assign values to variables.

Variables

Any Python interpreter can be used as a calculator:

3 + 5 * 4

23

This is great but not very interesting.

To do anything useful with data, we need to assign its value to a variable.

In Python, we can assign a value to a

variable, using the equals sign =.

For example, to assign value 60 to a variable weight_kg, we would execute:

weight_kg = 60

From now on, whenever we use weight_kg, Python will substitute the value we assigned to

it. In layman’s terms, a variable is a name for a value.

In Python, variable names:

- can include letters, digits, and underscores

- cannot start with a digit

- are case sensitive.

This means that, for example:

weight0is a valid variable name, whereas0weightis notweightandWeightare different variables

Types of data

Python knows various types of data. Three common ones are:

- integer numbers

- floating point numbers, and

- strings.

In the example above, variable weight_kg has an integer value of 60.

To create a variable with a floating point value, we can execute:

weight_kg = 60.0

And to create a string, we add single or double quotes around some text, for example:

weight_kg_text = 'weight in kilograms:'

Using Variables in Python

To display the value of a variable to the screen in Python, we can use the print function:

print(weight_kg)

60.0

We can display multiple things at once using only one print command:

print(weight_kg_text, weight_kg)

weight in kilograms: 60.0

Moreover, we can do arithmetic with variables right inside the print function:

print('weight in pounds:', 2.2 * weight_kg)

weight in pounds: 132.0

The above command, however, did not change the value of weight_kg:

print(weight_kg)

60.0

To change the value of the weight_kg variable, we have to

assign weight_kg a new value using the equals = sign:

weight_kg = 65.0

print('weight in kilograms is now:', weight_kg)

weight in kilograms is now: 65.0

Variables as Sticky Notes

A variable in Python is analogous to a sticky note with a name written on it: assigning a value to a variable is like putting that sticky note on a particular value.

Using this analogy, we can investigate how assigning a value to one variable does not change values of other, seemingly related, variables. For example, let’s store the subject’s weight in pounds in its own variable:

# There are 2.2 pounds per kilogram weight_lb = 2.2 * weight_kg print(weight_kg_text, weight_kg, 'and in pounds:', weight_lb)weight in kilograms: 65.0 and in pounds: 143.0

Similar to above, the expression

2.2 * weight_kgis evaluated to143.0, and then this value is assigned to the variableweight_lb(i.e. the sticky noteweight_lbis placed on143.0). At this point, each variable is “stuck” to completely distinct and unrelated values.Let’s now change

weight_kg:weight_kg = 100.0 print('weight in kilograms is now:', weight_kg, 'and weight in pounds is still:', weight_lb)weight in kilograms is now: 100.0 and weight in pounds is still: 143.0

Since

weight_lbdoesn’t “remember” where its value comes from, it is not updated when we changeweight_kg.

Check Your Understanding

What values do the variables

massandagehave after each of the following statements? Test your answer by executing the lines.mass = 47.5 age = 122 mass = mass * 2.0 age = age - 20Solution

`mass` holds a value of 47.5, `age` does not exist `mass` still holds a value of 47.5, `age` holds a value of 122 `mass` now has a value of 95.0, `age`'s value is still 122 `mass` still has a value of 95.0, `age` now holds 102

Sorting Out References

Python allows you to assign multiple values to multiple variables in one line by separating the variables and values with commas. What does the following program print out?

first, second = 'Grace', 'Hopper' third, fourth = second, first print(third, fourth)Solution

Hopper Grace

Key Points

Basic data types in Python include integers, strings, and floating-point numbers.

Use

variable = valueto assign a value to a variable in order to record it in memory.Variables are created on demand whenever a value is assigned to them.

Use

print(something)to display the value ofsomething.

Data Types and Type Conversion

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

What kinds of data do programs store?

How can I convert one type to another?

Objectives

Explain key differences between integers and floating point numbers.

Explain key differences between numbers and character strings.

Use built-in functions to convert between integers, floating point numbers, and strings.

Every value has a type.

- Every value in a program has a specific type.

- Integer (

int): counting numbers like 3 or -512. - Floating point number (

float): fractional numbers like 3.14159 or -2.5.- Integers are used to count, floats are used to measure.

- Character string (usually just called “string”,

str): text.- Written in either single quotes or double quotes (as long as they match).

- The quotation marks aren’t printed when the string is displayed.

Use the built-in function type to find the type of a value.

- Use the built-in function

typeto find out what type a value has. - Works on variables as well.

- But remember: the value has the type — the variable is just a label.

print(type(52))

<class 'int'>

fitness = 'average'

print(type(fitness))

<class 'str'>

Types control what operations can be done on values.

- A value’s type determines what the program can do to it.

print(5 - 3)

2

print('hello' - 'h')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-2-67f5626a1e07> in <module>()

----> 1 print('hello' - 'h')

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'str' and 'str'

Strings can be added and multiplied.

- “Adding” character strings concatenates them.

full_name = 'Ahmed' + ' ' + 'Walsh'

print(full_name)

Ahmed Walsh

- Multiplying a character string by an integer replicates it.

- Since multiplication is just repeated addition.

separator = '=' * 10

print(separator)

==========

Strings have a length (but numbers don’t).

- The built-in function

lencounts the number of characters in a string.

print(len(full_name))

11

- But numbers don’t have a length (not even zero).

print(len(52))

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-3-f769e8e8097d> in <module>()

----> 1 print(len(52))

TypeError: object of type 'int' has no len()

Must convert numbers to strings or vice versa when operating on them.

- Cannot add numbers and strings.

print(1 + 'A')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-4-fe4f54a023c6> in <module>()

----> 1 print(1 + '2')

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

- Not allowed because it’s ambiguous: should

1 + '2'be3or'12'? - Some types can be converted to other types by using the type name as a function.

print(1 + int('2'))

print(str(1) + '2')

3

12

Can mix integers and floats freely in operations.

- Integers and floating-point numbers can be mixed in arithmetic.

- Python automatically converts integers to floats as needed.

print('half is', 1 / 2.0)

print('three squared is', 3.0 ** 2)

half is 0.5

three squared is 9.0

Variables only change value when something is assigned to them.

- If we make one cell in a spreadsheet depend on another, and update the latter, the former updates automatically.

- This does not happen in programming languages.

first = 1

second = 5 * first

first = 2

print('first is', first, 'and second is', second)

first is 2 and second is 5

- The computer reads the value of

firstwhen doing the multiplication, creates a new value, and assigns it tosecond. - After that,

seconddoes not remember where it came from.

Choose a Type

What type of value (integer, floating point number, or character string) would you use to represent each of the following?

- Number of days since the start of the year.

- Time elapsed since the start of the year.

- Serial number of a piece of lab equipment.

- A lab specimen’s age.

- Current population of a city.

- Average population of a city over time.

Division Types

The

//operator calculates the whole-number result of division, while the ‘%’ operator calculates the remainder from division:print('5 // 3:', 5//3) print('5 % 3:', 5%3)5 // 3: 1 5 % 3: 2If

num_subjectsis the number of subjects taking part in a study, andnum_per_surveyis the number that can take part in a single survey, write an expression that calculates the number of surveys needed to reach everyone once.

Strings to Numbers

floatwill convert a string to a floating point number, andintwill convert a floating point number to an integer:print("string to float:", float("3.4")) print("float to int:", int(3.4))string to float:, 3.4 float to int:, 3Given that, what do you expect this program to do? What does it actually do? Why do you think it does that?

print("fractional string to int:", int("3.4"))

Arithmetic with Different Types

Which of the following will print 2.0? Note: there may be more than one right answer.

first = 1.0 second = "1" third = "1.1"

first + float(second)float(second) + float(third)first + int(third)first + int(float(third))int(first) + int(float(third))2.0 * secondSolution

Answer: 1 and 4

Complex Numbers

FIXME: introduce complex numbers

Key Points

Every value has a type.

Use the built-in function

typeto find the type of a value.Types control what operations can be done on values.

Strings can be added and multiplied.

Strings have a length (but numbers don’t).

Must convert numbers to strings or vice versa when operating on them.

Can mix integers and floats freely in operations.

Variables only change value when something is assigned to them.

Built-in Functions and Help

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I use built-in functions?

How can I find out what they do?

Objectives

Explain the purpose of functions.

Correctly call built-in Python functions.

Correctly nest calls to built-in functions.

Use help to display documentation for built-in functions.

A function may take zero or more arguments.

- We have seen some functions already — now let’s take a closer look.

- An argument is a value passed into a function.

lentakes exactly one.int,str, andfloatcreate a new value from an existing one.printtakes zero or more.printwith no arguments prints a blank line.- Must always use parentheses, even if they’re empty, so that Python knows a function is being called.

print('before')

print()

print('after')

before

after

Commonly-used built-in functions include max, min, and round.

- Use

maxto find the largest value of one or more values. - Use

minto find the smallest. - Both work on character strings as well as numbers.

- “Larger” and “smaller” use (0-9, A-Z, a-z) to compare letters.

print(max(1, 2, 3))

print(min('a', 'A', '0'))

3

0

Functions may only work for certain (combinations of) arguments.

maxandminmust be given at least one argument.- “Largest of the empty set” is a meaningless question.

- And they must be given things that can meaningfully be compared.

print(max(1, 'a'))

TypeError: unorderable types: str() > int()

Functions may have default values for some arguments.

roundwill round off a floating-point number.- By default, rounds to zero decimal places.

round(3.712)

4

- We can specify the number of decimal places we want.

round(3.712, 1)

3.7

Use the built-in function help to get help for a function.

- Every built-in function has online documentation.

help(round)

Help on built-in function round in module builtins:

round(...)

round(number[, ndigits]) -> number

Round a number to a given precision in decimal digits (default 0 digits).

This returns an int when called with one argument, otherwise the

same type as the number. ndigits may be negative.

The Jupyter Notebook has two ways to get help.

- Place the cursor inside the parenthesis of the function,

hold down

shift, and presstab. - Or type a function name with a question mark after it.

Every function returns something.

- Every function call produces some result.

- If the function doesn’t have a useful result to return,

it usually returns the special value

None.

result = print('example')

print('result of print is', result)

example

result of print is None

What Happens When

- Explain in simple terms the order of operations in the following program: when does the addition happen, when does the subtraction happen, when is each function called, etc.

- What is the final value of

radiance?radiance = 1.0 radiance = max(2.1, 2.0 + min(radiance, 1.1 * radiance - 0.5))

Spot the Difference

- Predict what each of the

- Does

max(len(rich), poor)run or produce an error message? If it runs, does its result make any sense?rich = "gold" poor = "tin" print(max(rich, poor)) print(max(len(rich), len(poor)))

Why Not?

Why don’t

maxandminreturnNonewhen they are given no arguments?

Key Points

A function may take zero or more arguments.

Commonly-used built-in functions include

max,min, andround.Functions may only work for certain (combinations of) arguments.

Functions may have default values for some arguments.

Use the built-in function

helpto get help for a function.The Jupyter Notebook has two ways to get help.

Every function returns something.

Error Messages

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

What kind of errors can occur in programs?

How can I identify errors when they occur?

Objectives

Read a traceback and determine the file, function, and line number on which the error occurred, the type of error, and the error message.

Correctly describe situations in which SyntaxError, IndentationError, NameError, IndexError, and FileNotFoundError occur.

Use comments to add documentation to programs.

# This sentence isn't executed by Python.

adjustment = 0.5 # Neither is this - anything after '#' is ignored.

Python reports a syntax error when it can’t understand the source of a program.

- Won’t even try to run the program if it can’t be parsed.

# Forgot to close the quotation marks around the string.

name = 'Feng

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literal

# An extra '=' in the assignment.

age = = 52

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

- Look more closely at the error message:

print("hello world"

File "<ipython-input-6-d1cc229bf815>", line 1

print ("hello world"

^

SyntaxError: unexpected EOF while parsing

- The message indicates a problem on first line of the input (“line 1”).

- In this case the “ipython-input” section of the file name tells us that we are working with input into IPython, the Python interpreter used by the Jupyter Notebook.

- The

-6-part of the filename indicates that the error occurred in cell 6 of our Notebook. - Next is the problematic line of code,

indicating the problem with a

^pointer.

Indentation is meaningful in Python.

- Python uses indentation to group sections of code together (which we will discuss later).

- If the indentation changes in a way that Python does not expect,

it reports an

IndentationError(which is a more specific kind of syntax error).

firstName="Jon"

lastName="Smith"

File "<ipython-input-7-f65f2962bf9c>", line 2

lastName="Smith"

^

IndentationError: unexpected indent

- This error can be fixed by removing the extra spaces at the beginning of the second line.

Python reports a runtime error when something goes wrong while a program is executing.

age = 53

remaining = 100 - aege # mis-spelled 'age'

NameError: name 'aege' is not defined

Fix syntax errors by reading the source and runtime errors by tracing execution.

FIXME: diagram of where each type of error occurs.

FIXME: this entire episode needs to move later (we can’t do IndentationError yet, or talk about the tracebacks until we’ve written functions).

Reading Error Messages

Read the traceback below, and identify the following:

- How many levels does the traceback have?

- What is the file name where the error occurred?

- What is the function name where the error occurred?

- On which line number in this function did the error occurr?

- What is the type of error?

- What is the error message?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- KeyError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-2-e4c4cbafeeb5> in <module>() 1 import errors_02 ----> 2 errors_02.print_friday_message() /Users/ghopper/thesis/code/errors_02.py in print_friday_message() 13 14 def print_friday_message(): ---> 15 print_message("Friday") /Users/ghopper/thesis/code/errors_02.py in print_message(day) 9 "sunday": "Aw, the weekend is almost over." 10 } ---> 11 print(messages[day]) 12 13 KeyError: 'Friday'

Identifying Syntax Errors

- Read the code below and try to identify what the errors are without running it.

- Run the code and read the error message. Is it a

SyntaxErroror anIndentationError?- Fix the error.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 until you have fixed all the errors.

def another_function print("Syntax errors are annoying.") print("But at least python tells us about them!") print("So they are usually not too hard to fix.")

Identifying Variable Name Errors

- Read the code below and try to identify what the errors are without running it.

- Run the code and read the error message. What type of

NameErrordo you think this is? Is it a string with no quotes, a misspelled variable, or a variable that should have been defined but was not?- Fix the error.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3, until you have fixed all the errors.

for number in range(10): # use a if the number is a multiple of 3, otherwise use b if (Number % 3) == 0: message = message + a else: message = message + "b" print(message)

Identifying Item Errors

- Read the code below and try to identify what the errors are without running it.

- Run the code, and read the error message. What type of error is it?

- Fix the error.

seasons = ['Spring', 'Summer', 'Fall', 'Winter'] print('My favorite season is ', seasons[4])

Key Points

Use comments to add documentation to programs.

Python reports a syntax error when it can’t understand the source of a program.

Indentation is meaningful in Python.

Python reports a runtime error when something goes wrong while a program is executing.

Fix syntax errors by reading the source code, and runtime errors by tracing the program’s execution.

Morning break

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

Objectives

Key Points

Libraries

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

How can I use software that other people have written?

How can I find out what that software does?

Objectives

Explain what software libraries are and why programmers create and use them.

Write programs that import and use libraries from Python’s standard library.

Find and read documentation for standard libraries interactively (in the interpreter) and online.

Most of the power of a programming language is in its libraries.

- A library is a collection of functions that can be used by other programs.

- May also contain data values (e.g., numerical constants).

- Library’s contents are supposed to be related, but there’s no way to enforce that.

- Python’s standard library is installed with it.

- Many additional libraries are available from PyPI (the Python Package Index).

- We will see later how to write new libraries.

A program must import a library in order to use it.

- Use

importto load a library into a program’s memory. - Then refer to things from the library as

library_name.thing_name.- Python uses

.to mean “part of”.

- Python uses

import math

print('pi is', math.pi)

print('cos(pi) is', math.cos(math.pi))

pi is 3.141592653589793

cos(pi) is -1.0

- Have to refer to each item with the library’s name.

math.cos(pi)won’t work: the reference topidoesn’t somehow “inherit” the function’s reference tomath.

Use help to find out more about a library’s contents.

- Works just like help for a function.

help(math)

Help on module math:

NAME

math

MODULE REFERENCE

http://docs.python.org/3.5/library/math

The following documentation is automatically generated from the Python

source files. It may be incomplete, incorrect or include features that

are considered implementation detail and may vary between Python

implementations. When in doubt, consult the module reference at the

location listed above.

DESCRIPTION

This module is always available. It provides access to the

mathematical functions defined by the C standard.

FUNCTIONS

acos(...)

acos(x)

Return the arc cosine (measured in radians) of x.

⋮ ⋮ ⋮

Import specific items from a library to shorten programs.

- Use

from...import...to load only specific items from a library. - Then refer to them directly without library name as prefix.

from math import cos, pi

print('cos(pi) is', cos(pi))

cos(pi) is -1.0

Create an alias for a library when importing it to shorten programs.

- Use

import...as...to give a library a short alias while importing it. - Then refer to items in the library using that shortened name.

import math as m

print('cos(pi) is', m.cos(m.pi))

cos(pi) is -1.0

- Commonly used for libraries that are frequently used or have long names.

- E.g.,

matplotlibplotting library is often aliased asmpl.

- E.g.,

- But can make programs harder to understand, since readers must learn your program’s aliases.

Locating the Right Library

You want to select a random value from your data:

ids = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

- What standard library would you most expect to help?

- Which function would you select from that library? Are there alternatives?

Exploring the Math Library

- What function from the

mathlibrary can you use to calculate a square root without usingsqrt?- Since the library contains this function, why does

sqrtexist?

When Is Help Available?

When a colleague of yours types

help(math), Python reports an error:NameError: name 'math' is not definedWhat has your colleague forgotten to do?

Importing With Aliases

- Fill in the blanks so that the program below prints

90.0.- Rewrite the program so that it uses

importwithoutas.- Which form do you find easier to read?

import math as m angle = ____.degrees(____.pi / 2) print(____)

Importing Specific Items

- Fill in the blanks so that the program below prints

90.0.- Do you find this easier to read than preceding versions?

- Why would’t programmers always use this form of

import?____ math import ____, ____ angle = degrees(pi / 2) print(angle)

Key Points

Most of the power of a programming language is in its libraries.

A program must import a library in order to use it.

Use

helpto find out more about a library’s contents.Import specific items from a library to shorten programs.

Create an alias for a library when importing it to shorten programs.

Analyzing Patient Data

Overview

Teaching: 40 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

How can I process tabular data files in Python?

Objectives

Explain what a library is and what libraries are used for.

Import a Python library and use the functions it contains.

Read tabular data from a file into a program.

Select individual values and subsections from data.

Perform operations on arrays of data.

Words are useful, but what’s more useful are the sentences and stories we build with them. Similarly, while a lot of powerful, general tools are built into Python, specialized tools built up from these basic units live in libraries that can be called upon when needed.

Loading data into Python

To begin processing inflammation data, we need to load it into Python. We can do that using a library called NumPy, which stands for Numerical Python. In general, you should use this library when you want to do fancy things with lots of numbers, especially if you have matrices or arrays. To tell Python that we’d like to start using NumPy, we need to import it:

import numpy

Importing a library is like getting a piece of lab equipment out of a storage locker and setting it up on the bench. Libraries provide additional functionality to the basic Python package, much like a new piece of equipment adds functionality to a lab space. Just like in the lab, importing too many libraries can sometimes complicate and slow down your programs - so we only import what we need for each program.

Once we’ve imported the library, we can ask the library to read our data file for us:

numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

array([[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 3., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 1., 2., ..., 1., 0., 1.],

[ 0., 1., 1., ..., 2., 1., 1.],

...,

[ 0., 1., 1., ..., 1., 1., 1.],

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 2., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 1., 1., 0.]])

The expression numpy.loadtxt(...) is a

function call

that asks Python to run the function loadtxt which

belongs to the numpy library.

This dotted notation

is used everywhere in Python: the thing that appears before the dot contains the thing that

appears after.

As an example, John Smith is the John that belongs to the Smith family.

We could use the dot notation to write his name smith.john,

just as loadtxt is a function that belongs to the numpy library.

numpy.loadtxt has two parameters: the name of the file

we want to read and the delimiter that separates values

on a line. These both need to be character strings

(or strings for short), so we put them in quotes.

Since we haven’t told it to do anything else with the function’s output,

the notebook displays it.

In this case,

that output is the data we just loaded.

By default,

only a few rows and columns are shown

(with ... to omit elements when displaying big arrays).

Note that, to save space when displaying NumPy arrays, Python does not show us trailing zeros,

so 1.0 becomes 1..

Our call to numpy.loadtxt read our file

but didn’t save the data in memory.

To do that,

we need to assign the array to a variable. In a similar manner to how we assign a single

value to a variable, we can also assign an array of values to a variable using the same syntax.

Let’s re-run numpy.loadtxt and save the returned data:

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

This statement doesn’t produce any output because we’ve assigned the output to the variable data.

If we want to check that the data have been loaded,

we can print the variable’s value:

print(data)

[[ 0. 0. 1. ..., 3. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 1. 2. ..., 1. 0. 1.]

[ 0. 1. 1. ..., 2. 1. 1.]

...,

[ 0. 1. 1. ..., 1. 1. 1.]

[ 0. 0. 0. ..., 0. 2. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 1. ..., 1. 1. 0.]]

Now that the data are in memory,

we can manipulate them.

First,

let’s ask what type of thing data refers to:

print(type(data))

<class 'numpy.ndarray'>

The output tells us that data currently refers to

an N-dimensional array, the functionality for which is provided by the NumPy library.

These data correspond to arthritis patients’ inflammation.

The rows are the individual patients, and the columns

are their daily inflammation measurements.

Data Type

A Numpy array contains one or more elements of the same type. The

typefunction will only tell you that a variable is a NumPy array but won’t tell you the type of thing inside the array. We can find out the type of the data contained in the NumPy array.print(data.dtype)float64This tells us that the NumPy array’s elements are floating-point numbers.

With the following command, we can see the array’s shape:

print(data.shape)

(60, 40)

The output tells us that the data array variable contains 60 rows and 40 columns. When we

created the variable data to store our arthritis data, we did not only create the array; we also

created information about the array, called members or

attributes. This extra information describes data in the same way an adjective describes a noun.

data.shape is an attribute of data which describes the dimensions of data. We use the same

dotted notation for the attributes of variables that we use for the functions in libraries because

they have the same part-and-whole relationship.

If we want to get a single number from the array, we must provide an index in square brackets after the variable name, just as we do in math when referring to an element of a matrix. Our inflammation data has two dimensions, so we will need to use two indices to refer to one specific value:

print('first value in data:', data[0, 0])

first value in data: 0.0

print('middle value in data:', data[30, 20])

middle value in data: 13.0

The expression data[30, 20] accesses the element at row 30, column 20. While this expression may

not surprise you,

data[0, 0] might.

Programming languages like Fortran, MATLAB and R start counting at 1

because that’s what human beings have done for thousands of years.

Languages in the C family (including C++, Java, Perl, and Python) count from 0

because it represents an offset from the first value in the array (the second

value is offset by one index from the first value). This is closer to the way

that computers represent arrays (if you are interested in the historical

reasons behind counting indices from zero, you can read

Mike Hoye’s blog post).

As a result,

if we have an M×N array in Python,

its indices go from 0 to M-1 on the first axis

and 0 to N-1 on the second.

It takes a bit of getting used to,

but one way to remember the rule is that

the index is how many steps we have to take from the start to get the item we want.

In the Corner

What may also surprise you is that when Python displays an array, it shows the element with index

[0, 0]in the upper left corner rather than the lower left. This is consistent with the way mathematicians draw matrices but different from the Cartesian coordinates. The indices are (row, column) instead of (column, row) for the same reason, which can be confusing when plotting data.

Slicing data

An index like [30, 20] selects a single element of an array,

but we can select whole sections as well.

For example,

we can select the first ten days (columns) of values

for the first four patients (rows) like this:

print(data[0:4, 0:10])

[[ 0. 0. 1. 3. 1. 2. 4. 7. 8. 3.]

[ 0. 1. 2. 1. 2. 1. 3. 2. 2. 6.]

[ 0. 1. 1. 3. 3. 2. 6. 2. 5. 9.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 0. 4. 2. 2. 1. 6. 7.]]

The slice 0:4 means, “Start at index 0 and go up to,

but not including, index 4”. Again, the up-to-but-not-including takes a bit of getting used to,

but the rule is that the difference between the upper and lower bounds is the number of values in

the slice.

We don’t have to start slices at 0:

print(data[5:10, 0:10])

[[ 0. 0. 1. 2. 2. 4. 2. 1. 6. 4.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 2. 4. 2. 2. 5. 5. 8.]

[ 0. 0. 1. 2. 3. 1. 2. 3. 5. 3.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 3. 1. 5. 6. 5. 5. 8.]

[ 0. 1. 1. 2. 1. 3. 5. 3. 5. 8.]]

We also don’t have to include the upper and lower bound on the slice. If we don’t include the lower bound, Python uses 0 by default; if we don’t include the upper, the slice runs to the end of the axis, and if we don’t include either (i.e., if we use ‘:’ on its own), the slice includes everything:

small = data[:3, 36:]

print('small is:')

print(small)

The above example selects rows 0 through 2 and columns 36 through to the end of the array.

small is:

[[ 2. 3. 0. 0.]

[ 1. 1. 0. 1.]

[ 2. 2. 1. 1.]]

Analyzing data

NumPy has several useful functions that take an array as input to perform operations on its values.

If we want to find the average inflammation for all patients on

all days, for example, we can ask NumPy to compute data’s mean value:

print(numpy.mean(data))

6.14875

mean is a function that takes

an array as an argument.

Not All Functions Have Input

Generally, a function uses inputs to produce outputs. However, some functions produce outputs without needing any input. For example, checking the current time doesn’t require any input.

import time print(time.ctime())Sat Mar 26 13:07:33 2016For functions that don’t take in any arguments, we still need parentheses (

()) to tell Python to go and do something for us.

Let’s use three other NumPy functions to get some descriptive values about the dataset. We’ll also use multiple assignment, a convenient Python feature that will enable us to do this all in one line.

maxval, minval, stdval = numpy.max(data), numpy.min(data), numpy.std(data)

print('maximum inflammation:', maxval)

print('minimum inflammation:', minval)

print('standard deviation:', stdval)

Here we’ve assigned the return value from numpy.max(data) to the variable maxval, the value

from numpy.min(data) to minval, and so on.

maximum inflammation: 20.0

minimum inflammation: 0.0

standard deviation: 4.61383319712

Mystery Functions in IPython

How did we know what functions NumPy has and how to use them? If you are working in IPython or in a Jupyter Notebook, there is an easy way to find out. If you type the name of something followed by a dot, then you can use tab completion (e.g. type

numpy.and then press Tab) to see a list of all functions and attributes that you can use. After selecting one, you can also add a question mark (e.g.numpy.cumprod?), and IPython will return an explanation of the method! This is the same as doinghelp(numpy.cumprod). Similarly, if you are using the “plain vanilla” Python interpreter, you can typenumpy.and press the Tab key twice for a listing of what is available. You can then use thehelp()function to see an explanation of the function you’re interested in, for example:help(numpy.cumprod).

When analyzing data, though, we often want to look at variations in statistical values, such as the maximum inflammation per patient or the average inflammation per day. One way to do this is to create a new temporary array of the data we want, then ask it to do the calculation:

patient_0 = data[0, :] # 0 on the first axis (rows), everything on the second (columns)

print('maximum inflammation for patient 0:', numpy.max(patient_0))

maximum inflammation for patient 0: 18.0

Everything in a line of code following the ‘#’ symbol is a comment that is ignored by Python. Comments allow programmers to leave explanatory notes for other programmers or their future selves.

We don’t actually need to store the row in a variable of its own. Instead, we can combine the selection and the function call:

print('maximum inflammation for patient 2:', numpy.max(data[2, :]))

maximum inflammation for patient 2: 19.0

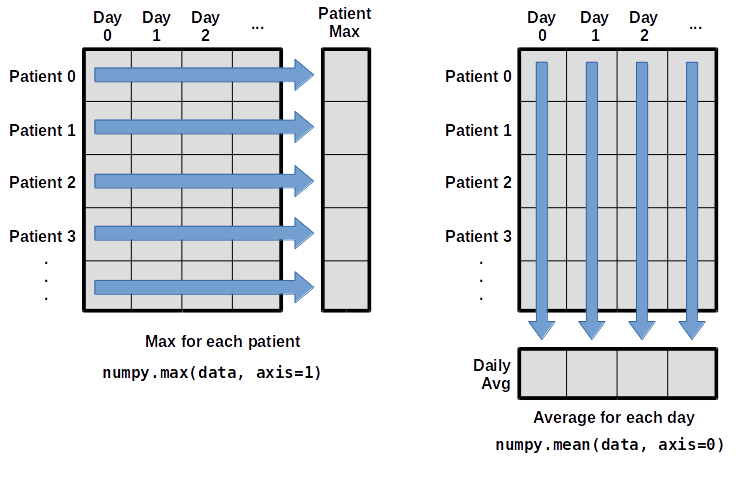

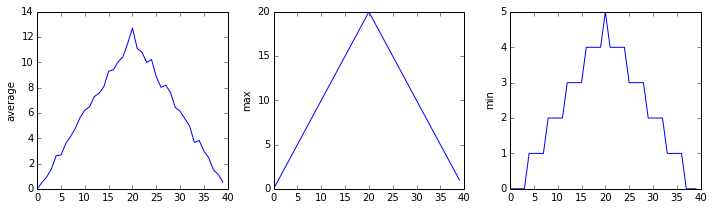

What if we need the maximum inflammation for each patient over all days (as in the next diagram on the left) or the average for each day (as in the diagram on the right)? As the diagram below shows, we want to perform the operation across an axis:

To support this functionality, most array functions allow us to specify the axis we want to work on. If we ask for the average across axis 0 (rows in our 2D example), we get:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

[ 0. 0.45 1.11666667 1.75 2.43333333 3.15

3.8 3.88333333 5.23333333 5.51666667 5.95 5.9

8.35 7.73333333 8.36666667 9.5 9.58333333

10.63333333 11.56666667 12.35 13.25 11.96666667

11.03333333 10.16666667 10. 8.66666667 9.15 7.25

7.33333333 6.58333333 6.06666667 5.95 5.11666667 3.6

3.3 3.56666667 2.48333333 1.5 1.13333333

0.56666667]

As a quick check, we can ask this array what its shape is:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=0).shape)

(40,)

The expression (40,) tells us we have an N×1 vector,

so this is the average inflammation per day for all patients.

If we average across axis 1 (columns in our 2D example), we get:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=1))

[ 5.45 5.425 6.1 5.9 5.55 6.225 5.975 6.65 6.625 6.525

6.775 5.8 6.225 5.75 5.225 6.3 6.55 5.7 5.85 6.55

5.775 5.825 6.175 6.1 5.8 6.425 6.05 6.025 6.175 6.55

6.175 6.35 6.725 6.125 7.075 5.725 5.925 6.15 6.075 5.75

5.975 5.725 6.3 5.9 6.75 5.925 7.225 6.15 5.95 6.275 5.7

6.1 6.825 5.975 6.725 5.7 6.25 6.4 7.05 5.9 ]

which is the average inflammation per patient across all days.

Slicing Strings

A section of an array is called a slice. We can take slices of character strings as well:

element = 'oxygen' print('first three characters:', element[0:3]) print('last three characters:', element[3:6])first three characters: oxy last three characters: genWhat is the value of

element[:4]? What aboutelement[4:]? Orelement[:]?Solution

oxyg en oxygenWhat is

element[-1]? What iselement[-2]?Solution

n eGiven those answers, explain what

element[1:-1]does.Solution

Creates a substring from index 1 up to (not including) the final index, effectively removing the first and last letters from ‘oxygen’

How can we rewrite the slice for getting the last three characters of

element, so that it works even if we assign a different string toelement? Test your solution with the following strings:carpentry,clone,hi.Solution

element = 'oxygen' print('last three characters:', element[-3:]) element = 'carpentry' print('last three characters:', element[-3:]) element = 'clone' print('last three characters:', element[-3:]) element = 'hi' print('last three characters:', element[-3:])last three characters: gen last three characters: try last three characters: one last three characters: hi

Thin Slices

The expression

element[3:3]produces an empty string, i.e., a string that contains no characters. Ifdataholds our array of patient data, what doesdata[3:3, 4:4]produce? What aboutdata[3:3, :]?Solution

array([], shape=(0, 0), dtype=float64) array([], shape=(0, 40), dtype=float64)

Stacking Arrays

Arrays can be concatenated and stacked on top of one another, using NumPy’s

vstackandhstackfunctions for vertical and horizontal stacking, respectively.import numpy A = numpy.array([[1,2,3], [4,5,6], [7, 8, 9]]) print('A = ') print(A) B = numpy.hstack([A, A]) print('B = ') print(B) C = numpy.vstack([A, A]) print('C = ') print(C)A = [[1 2 3] [4 5 6] [7 8 9]] B = [[1 2 3 1 2 3] [4 5 6 4 5 6] [7 8 9 7 8 9]] C = [[1 2 3] [4 5 6] [7 8 9] [1 2 3] [4 5 6] [7 8 9]]Write some additional code that slices the first and last columns of

A, and stacks them into a 3x2 array. Make sure toSolution

A ‘gotcha’ with array indexing is that singleton dimensions are dropped by default. That means

A[:, 0]is a one dimensional array, which won’t stack as desired. To preserve singleton dimensions, the index itself can be a slice or array. For example,A[:, :1]returns a two dimensional array with one singleton dimension (i.e. a column vector).D = numpy.hstack((A[:, :1], A[:, -1:])) print('D = ') print(D)D = [[1 3] [4 6] [7 9]]Solution

An alternative way to achieve the same result is to use Numpy’s delete function to remove the second column of A.

D = numpy.delete(A, 1, 1) print('D = ') print(D)D = [[1 3] [4 6] [7 9]]

Change In Inflammation

The patient data is longitudinal in the sense that each row represents a series of observations relating to one individual. This means that the change in inflammation over time is a meaningful concept. Let’s find out how to calculate changes in the data contained in an array with NumPy.

The

numpy.diff()function takes an array and returns the differences between two successive values. Let’s use it to examine the changes each day across the first week of patient 3 from our inflammation dataset.patient3_week1 = data[3, :7] print(patient3_week1)[0. 0. 2. 0. 4. 2. 2.]Calling

numpy.diff(patient3_week1)would do the following calculations[ 0 - 0, 2 - 0, 0 - 2, 4 - 0, 2 - 4, 2 - 2 ]and return the 6 difference values in a new array.

numpy.diff(patient3_week1)array([ 0., 2., -2., 4., -2., 0.])Note that the array of differences is shorter by one element (length 6).

When calling

numpy.diffwith a multi-dimensional array, anaxisargument may be passed to the function to specify which axis to process. When applyingnumpy.diffto our 2D inflammation arraydata, which axis would we specify?Solution

Since the row axis (0) is patients, it does not make sense to get the difference between two arbitrary patients. The column axis (1) is in days, so the difference is the change in inflammation – a meaningful concept.

numpy.diff(data, axis=1)If the shape of an individual data file is

(60, 40)(60 rows and 40 columns), what would the shape of the array be after you run thediff()function and why?Solution

The shape will be

(60, 39)because there is one fewer difference between columns than there are columns in the data.How would you find the largest change in inflammation for each patient? Does it matter if the change in inflammation is an increase or a decrease?

Solution

By using the

numpy.max()function after you apply thenumpy.diff()function, you will get the largest difference between days.numpy.max(numpy.diff(data, axis=1), axis=1)array([ 7., 12., 11., 10., 11., 13., 10., 8., 10., 10., 7., 7., 13., 7., 10., 10., 8., 10., 9., 10., 13., 7., 12., 9., 12., 11., 10., 10., 7., 10., 11., 10., 8., 11., 12., 10., 9., 10., 13., 10., 7., 7., 10., 13., 12., 8., 8., 10., 10., 9., 8., 13., 10., 7., 10., 8., 12., 10., 7., 12.])If inflammation values decrease along an axis, then the difference from one element to the next will be negative. If you are interested in the magnitude of the change and not the direction, the

numpy.absolute()function will provide that.Notice the difference if you get the largest absolute difference between readings.

numpy.max(numpy.absolute(numpy.diff(data, axis=1)), axis=1)array([ 12., 14., 11., 13., 11., 13., 10., 12., 10., 10., 10., 12., 13., 10., 11., 10., 12., 13., 9., 10., 13., 9., 12., 9., 12., 11., 10., 13., 9., 13., 11., 11., 8., 11., 12., 13., 9., 10., 13., 11., 11., 13., 11., 13., 13., 10., 9., 10., 10., 9., 9., 13., 10., 9., 10., 11., 13., 10., 10., 12.])

Key Points

Import a library into a program using

import libraryname.Use the

numpylibrary to work with arrays in Python.The expression

array.shapegives the shape of an array.Use

array[x, y]to select a single element from a 2D array.Array indices start at 0, not 1.

Use

low:highto specify aslicethat includes the indices fromlowtohigh-1.Use

# some kind of explanationto add comments to programs.Use

numpy.mean(array),numpy.max(array), andnumpy.min(array)to calculate simple statistics.Use

numpy.mean(array, axis=0)ornumpy.mean(array, axis=1)to calculate statistics across the specified axis.

Visualizing Tabular Data

Overview

Teaching: 25 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can I visualize tabular data in Python?

How can I group several plots together?

Objectives

Plot simple graphs from data.

Group several graphs in a single figure.

Visualizing data

The mathematician Richard Hamming once said, “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers,” and

the best way to develop insight is often to visualize data. Visualization deserves an entire

lecture of its own, but we can explore a few features of Python’s matplotlib library here. While

there is no official plotting library, matplotlib is the de facto standard. First, we will

import the pyplot module from matplotlib and use two of its functions to create and display a

heat map of our data:

import matplotlib.pyplot

image = matplotlib.pyplot.imshow(data)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

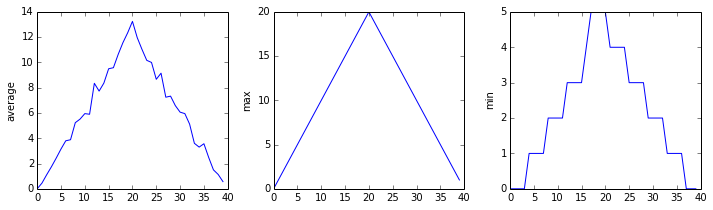

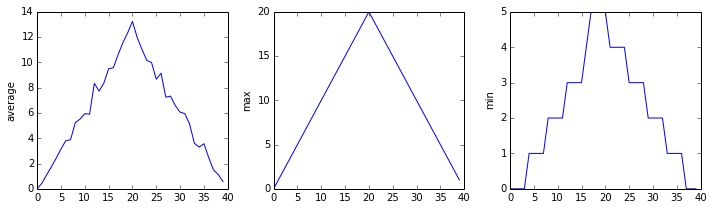

Blue pixels in this heat map represent low values, while yellow pixels represent high values. As we can see, inflammation rises and falls over a 40-day period. Let’s take a look at the average inflammation over time:

ave_inflammation = numpy.mean(data, axis=0)

ave_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(ave_inflammation)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Here, we have put the average inflammation per day across all patients in the variable

ave_inflammation, then asked matplotlib.pyplot to create and display a line graph of those

values. The result is a roughly linear rise and fall, which is suspicious: we might instead expect

a sharper rise and slower fall. Let’s have a look at two other statistics:

max_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

min_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

The maximum value rises and falls smoothly, while the minimum seems to be a step function. Neither trend seems particularly likely, so either there’s a mistake in our calculations or something is wrong with our data. This insight would have been difficult to reach by examining the numbers themselves without visualization tools.

Grouping plots

You can group similar plots in a single figure using subplots.

This script below uses a number of new commands. The function matplotlib.pyplot.figure()

creates a space into which we will place all of our plots. The parameter figsize

tells Python how big to make this space. Each subplot is placed into the figure using

its add_subplot method. The add_subplot method takes 3

parameters. The first denotes how many total rows of subplots there are, the second parameter

refers to the total number of subplot columns, and the final parameter denotes which subplot

your variable is referencing (left-to-right, top-to-bottom). Each subplot is stored in a

different variable (axes1, axes2, axes3). Once a subplot is created, the axes can

be titled using the set_xlabel() command (or set_ylabel()).

Here are our three plots side by side:

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

matplotlib.pyplot.savefig('inflammation.png')

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

The call to loadtxt reads our data,

and the rest of the program tells the plotting library

how large we want the figure to be,

that we’re creating three subplots,

what to draw for each one,

and that we want a tight layout.

(If we leave out that call to fig.tight_layout(),

the graphs will actually be squeezed together more closely.)

The call to savefig stores the plot as a graphics file. This can be

a convenient way to store your plots for use in other documents, web

pages etc. The graphics format is automatically determined by

Matplotlib from the file name ending we specify; here PNG from

‘inflammation.png’. Matplotlib supports many different graphics

formats, including SVG, PDF, and JPEG.

Importing libraries with shortcuts

In this lesson we use the

import matplotlib.pyplotsyntax to import thepyplotmodule ofmatplotlib. However, shortcuts such asimport matplotlib.pyplot as pltare frequently used. Importingpyplotthis way means that after the initial import, rather than writingmatplotlib.pyplot.plot(...), you can now writeplt.plot(...). Another common convention is to use the shortcutimport numpy as npwhen importing the NumPy library. We then can writenp.loadtxt(...)instead ofnumpy.loadtxt(...), for example.Some people prefer these shortcuts as it is quicker to type and results in shorter lines of code - especially for libraries with long names! You will frequently see Python code online using a

pyplotfunction withplt, or a NumPy function withnp, and it’s because they’ve used this shortcut. It makes no difference which approach you choose to take, but you must be consistent as if you useimport matplotlib.pyplot as pltthenmatplotlib.pyplot.plot(...)will not work, and you must useplt.plot(...)instead. Because of this, when working with other people it is important you agree on how libraries are imported.

Plot Scaling

Why do all of our plots stop just short of the upper end of our graph?

Solution

Because matplotlib normally sets x and y axes limits to the min and max of our data (depending on data range)

If we want to change this, we can use the

set_ylim(min, max)method of each ‘axes’, for example:axes3.set_ylim(0,6)Update your plotting code to automatically set a more appropriate scale. (Hint: you can make use of the

maxandminmethods to help.)Solution

# One method axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) axes3.set_ylim(0,6)Solution

# A more automated approach min_data = numpy.min(data, axis=0) axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(min_data) axes3.set_ylim(numpy.min(min_data), numpy.max(min_data) * 1.1)

Drawing Straight Lines

In the center and right subplots above, we expect all lines to look like step functions because non-integer value are not realistic for the minimum and maximum values. However, you can see that the lines are not always vertical or horizontal, and in particular the step function in the subplot on the right looks slanted. Why is this?

Solution

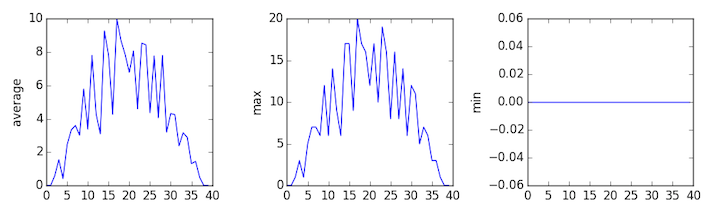

Because matplotlib interpolates (draws a straight line) between the points. One way to do avoid this is to use the Matplotlib

drawstyleoption:import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',') fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0)) axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1) axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2) axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3) axes1.set_ylabel('average') axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') axes2.set_ylabel('max') axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') fig.tight_layout() matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Make Your Own Plot

Create a plot showing the standard deviation (

numpy.std) of the inflammation data for each day across all patients.Solution

std_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.std(data, axis=0)) matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Moving Plots Around

Modify the program to display the three plots on top of one another instead of side by side.

Solution

import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',') # change figsize (swap width and height) fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(3.0, 10.0)) # change add_subplot (swap first two parameters) axes1 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 1) axes2 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 2) axes3 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 3) axes1.set_ylabel('average') axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0)) axes2.set_ylabel('max') axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0)) axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) fig.tight_layout() matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Key Points

Use the

pyplotmodule from thematplotliblibrary for creating simple visualizations.

Storing Multiple Values in Lists

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can I store many values together?

Objectives

Explain what a list is.

Create and index lists of simple values.

Change the values of individual elements

Append values to an existing list

Reorder and slice list elements

Create and manipulate nested lists

In the previous episode, we analyzed a single file with inflammation data. Our goal, however, is to process all inflammation data we’ve got, which means that we still have eleven more files to go!

The natural first step is to collect the names of all the files that we have to process. In Python, a list is a way to store multiple values together. In this episode, we will learn how to store multiple values in a list as well as how to work with lists.

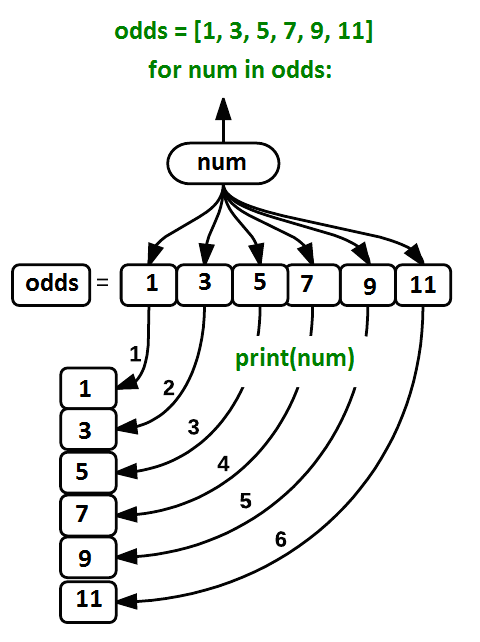

Python lists

Unlike NumPy arrays, lists are built into the language so we don’t have to load a library to use them. We create a list by putting values inside square brackets and separating the values with commas:

odds = [1, 3, 5, 7]

print('odds are:', odds)

odds are: [1, 3, 5, 7]

We can access elements of a list using indices – numbered positions of elements in the list. These positions are numbered starting at 0, so the first element has an index of 0.

print('first element:', odds[0])

print('last element:', odds[3])

print('"-1" element:', odds[-1])

first element: 1

last element: 7

"-1" element: 7

Yes, we can use negative numbers as indices in Python. When we do so, the index -1 gives us the

last element in the list, -2 the second to last, and so on.

Because of this, odds[3] and odds[-1] point to the same element here.

There is one important difference between lists and strings: we can change the values in a list, but we cannot change individual characters in a string. For example:

names = ['Curie', 'Darwing', 'Turing'] # typo in Darwin's name

print('names is originally:', names)

names[1] = 'Darwin' # correct the name

print('final value of names:', names)

names is originally: ['Curie', 'Darwing', 'Turing']

final value of names: ['Curie', 'Darwin', 'Turing']

works, but:

name = 'Darwin'

name[0] = 'd'

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-8-220df48aeb2e> in <module>()

1 name = 'Darwin'

----> 2 name[0] = 'd'

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

does not.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

Data which can be modified in place is called mutable, while data which cannot be modified is called immutable. Strings and numbers are immutable. This does not mean that variables with string or number values are constants, but when we want to change the value of a string or number variable, we can only replace the old value with a completely new value.

Lists and arrays, on the other hand, are mutable: we can modify them after they have been created. We can change individual elements, append new elements, or reorder the whole list. For some operations, like sorting, we can choose whether to use a function that modifies the data in-place or a function that returns a modified copy and leaves the original unchanged.

Be careful when modifying data in-place. If two variables refer to the same list, and you modify the list value, it will change for both variables!

salsa = ['peppers', 'onions', 'cilantro', 'tomatoes'] my_salsa = salsa # <-- my_salsa and salsa point to the *same* list data in memory salsa[0] = 'hot peppers' print('Ingredients in my salsa:', my_salsa)Ingredients in my salsa: ['hot peppers', 'onions', 'cilantro', 'tomatoes']If you want variables with mutable values to be independent, you must make a copy of the value when you assign it.

salsa = ['peppers', 'onions', 'cilantro', 'tomatoes'] my_salsa = list(salsa) # <-- makes a *copy* of the list salsa[0] = 'hot peppers' print('Ingredients in my salsa:', my_salsa)Ingredients in my salsa: ['peppers', 'onions', 'cilantro', 'tomatoes']Because of pitfalls like this, code which modifies data in place can be more difficult to understand. However, it is often far more efficient to modify a large data structure in place than to create a modified copy for every small change. You should consider both of these aspects when writing your code.

Nested Lists

Since a list can contain any Python variables, it can even contain other lists.

For example, we could represent the products in the shelves of a small grocery shop:

x = [['pepper', 'zucchini', 'onion'], ['cabbage', 'lettuce', 'garlic'], ['apple', 'pear', 'banana']]Here is a visual example of how indexing a list of lists

xworks:Using the previously declared list

x, these would be the results of the index operations shown in the image:print([x[0]])[['pepper', 'zucchini', 'onion']]print(x[0])['pepper', 'zucchini', 'onion']print(x[0][0])'pepper'Thanks to Hadley Wickham for the image above.

Heterogeneous Lists

Lists in Python can contain elements of different types. Example:

sample_ages = [10, 12.5, 'Unknown']

There are many ways to change the contents of lists besides assigning new values to individual elements:

odds.append(11)

print('odds after adding a value:', odds)

odds after adding a value: [1, 3, 5, 7, 11]

removed_element = odds.pop(0)

print('odds after removing the first element:', odds)

print('removed_element:', removed_element)

odds after removing the first element: [3, 5, 7, 11]

removed_element: 1

odds.reverse()

print('odds after reversing:', odds)

odds after reversing: [11, 7, 5, 3]

While modifying in place, it is useful to remember that Python treats lists in a slightly counter-intuitive way.

As we saw earlier, when we modified the salsa list item in-place, if we make a list, (attempt to)

copy it and then modify this list, we can cause all sorts of trouble. This also applies to modifying

the list using the above functions:

odds = [1, 3, 5, 7]

primes = odds

primes.append(2)

print('primes:', primes)

print('odds:', odds)

primes: [1, 3, 5, 7, 2]

odds: [1, 3, 5, 7, 2]

This is because Python stores a list in memory, and then can use multiple names to refer to the

same list. If all we want to do is copy a (simple) list, we can again use the list function, so we

do not modify a list we did not mean to:

odds = [1, 3, 5, 7]

primes = list(odds)

primes.append(2)

print('primes:', primes)

print('odds:', odds)

primes: [1, 3, 5, 7, 2]

odds: [1, 3, 5, 7]

Subsets of lists and strings can be accessed by specifying ranges of values in brackets, similar to how we accessed ranges of positions in a NumPy array. This is commonly referred to as “slicing” the list/string.

binomial_name = 'Drosophila melanogaster'

group = binomial_name[0:10]

print('group:', group)

species = binomial_name[11:23]

print('species:', species)

chromosomes = ['X', 'Y', '2', '3', '4']

autosomes = chromosomes[2:5]

print('autosomes:', autosomes)

last = chromosomes[-1]

print('last:', last)

group: Drosophila

species: melanogaster

autosomes: ['2', '3', '4']

last: 4

Slicing From the End

Use slicing to access only the last four characters of a string or entries of a list.

string_for_slicing = 'Observation date: 02-Feb-2013' list_for_slicing = [['fluorine', 'F'], ['chlorine', 'Cl'], ['bromine', 'Br'], ['iodine', 'I'], ['astatine', 'At']]'2013' [['chlorine', 'Cl'], ['bromine', 'Br'], ['iodine', 'I'], ['astatine', 'At']]Would your solution work regardless of whether you knew beforehand the length of the string or list (e.g. if you wanted to apply the solution to a set of lists of different lengths)? If not, try to change your approach to make it more robust.

Hint: Remember that indices can be negative as well as positive

Solution

Use negative indices to count elements from the end of a container (such as list or string):

string_for_slicing[-4:] list_for_slicing[-4:]

Non-Continuous Slices

So far we’ve seen how to use slicing to take single blocks of successive entries from a sequence. But what if we want to take a subset of entries that aren’t next to each other in the sequence?

You can achieve this by providing a third argument to the range within the brackets, called the step size. The example below shows how you can take every third entry in a list:

primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37] subset = primes[0:12:3] print('subset', subset)subset [2, 7, 17, 29]Notice that the slice taken begins with the first entry in the range, followed by entries taken at equally-spaced intervals (the steps) thereafter. If you wanted to begin the subset with the third entry, you would need to specify that as the starting point of the sliced range:

primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37] subset = primes[2:12:3] print('subset', subset)subset [5, 13, 23, 37]Use the step size argument to create a new string that contains only every other character in the string “In an octopus’s garden in the shade”. Start with creating a variable to hold the string:

beatles = "In an octopus's garden in the shade"What slice of

beatleswill produce the following output (i.e., the first character, third character, and every other character through the end of the string)?I notpssgre ntesaeSolution

To obtain every other character you need to provide a slice with the step size of 2:

beatles[0:35:2]You can also leave out the beginning and end of the slice to take the whole string and provide only the step argument to go every second element:

beatles[::2]

If you want to take a slice from the beginning of a sequence, you can omit the first index in the range:

date = 'Monday 4 January 2016'

day = date[0:6]

print('Using 0 to begin range:', day)

day = date[:6]

print('Omitting beginning index:', day)

Using 0 to begin range: Monday

Omitting beginning index: Monday

And similarly, you can omit the ending index in the range to take a slice to the very end of the sequence:

months = ['jan', 'feb', 'mar', 'apr', 'may', 'jun', 'jul', 'aug', 'sep', 'oct', 'nov', 'dec']

sond = months[8:12]

print('With known last position:', sond)

sond = months[8:len(months)]

print('Using len() to get last entry:', sond)

sond = months[8:]

print('Omitting ending index:', sond)

With known last position: ['sep', 'oct', 'nov', 'dec']

Using len() to get last entry: ['sep', 'oct', 'nov', 'dec']

Omitting ending index: ['sep', 'oct', 'nov', 'dec']

Overloading

+usually means addition, but when used on strings or lists, it means “concatenate”. Given that, what do you think the multiplication operator*does on lists? In particular, what will be the output of the following code?counts = [2, 4, 6, 8, 10] repeats = counts * 2 print(repeats)

[2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10][4, 8, 12, 16, 20][[2, 4, 6, 8, 10],[2, 4, 6, 8, 10]][2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20]The technical term for this is operator overloading: a single operator, like

+or*, can do different things depending on what it’s applied to.Solution

The multiplication operator

*used on a list replicates elements of the list and concatenates them together:[2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10]It’s equivalent to:

counts + counts

Key Points

[value1, value2, value3, ...]creates a list.Lists can contain any Python object, including lists (i.e., list of lists).

Lists are indexed and sliced with square brackets (e.g., list[0] and list[2:9]), in the same way as strings and arrays.

Lists are mutable (i.e., their values can be changed in place).

Strings are immutable (i.e., the characters in them cannot be changed).

Sets (Kai)

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

What is a set, and how do I use it?

Objectives

Explain how sets work.

Learn about set operations

A set keeps an unsorted unique collection of things.

- Different from lists

- Lists have a defined order of elements, sets are unordered.

- Lists can contain the same value multiple times, sets do not.

- Sets have a number of fast operations you can use to compare or combine them.

- Sets are great to keep track of things where order an count don’t matter.

- If you put a value that is already in a set into that set again, the set will not change.

beatles = set(['John', 'Paul', 'George', 'Ringo'])

print('Beatles:', beatles)

print('length:', len(beatles))

beatles.add('Ringo')

print('Beatles:', beatles)

print('length:', len(beatles))

Beatles: {'John', 'Ringo', 'Paul', 'George'}

length: 4

Beatles: {'John', 'Ringo', 'Paul', 'George'}

length: 4

Use in to check if something is in a set

Sets allow for efficient check of members.

print('Ringo is one of the Beatles:', 'Ringo' in beatles)

print('Keith is one of the Beatles:', 'Keith' in beatles)

Ringo is one of the Beatles: True

Keith is one of the Beatles: False

You can add values to the set by using add()

beatles.add('Pete')

print('beatles is now:', beatles)

beatles is now: {'Pete', 'John', 'Ringo', 'Paul', 'George'}

You can remove values from the set by using remove()

beatles.remove('Pete')

print('beatles is now:', beatles)

beatles is now: {'John', 'Ringo', 'Paul', 'George'}

Multiple sets can be combined using union()

odd = set([1, 3, 5, 7, 9])

even = set([2, 4, 6, 8, 10])

all_numbers = odd.union(even)

print('Odd numbers:', odd)

print('Even numbers:', even)

print('All numbers:', all_numbers)

Odd numbers: {1, 3, 5, 9, 7}

Even numbers: {8, 2, 10, 4, 6}

All numbers: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}

Sets are unordered

As sets are unordered, the order of the elements can be different when you print this.

You can intersect two sets

This gives a new set containing only members existing in both sets

primes = set([2, 3, 5, 7])

odd_primes = primes.intersection(odd)

print('Primes that are also odd numbers:', odd_primes)

Primes that are also odd numbers: {3, 5, 7}

You can get the difference between to sets

This gives a new set containing all members of the first set not in the second set

even_non_primes = even.difference(primes)

print('Even numbers that are not prime numbers:', even_non_primes)

Even numbers that are not prime numbers: {8, 10, 4, 6}

For difference(), the order matters

Using the same sets in a different order gives a different result.

uneven_primes = primes.difference(even)

print('Primes that are not even:', uneven_primes)

Primes that are not even: {3, 5, 7}

Convert to a list and sort to get sorted output

sorted_primes = list(primes)

sorted_primes.sort()

print('Sorted primes:', sorted_primes)

Sorted primes: [2, 3, 5, 7]

Initialising

What does the following program print?

letters = set('Hello world!') sorted_letters = list(letters) sorted_letters.sort() print('Letters in greeting:', sorted_letters)

Fill in the Blanks

Fill in the blanks so that the program below produces the output shown.

multiples_of_two = set([2, 4, 6, 8, 10]) multiples_of_three = set([3, 6, 9]) result1 = multiples_of_two._______(multiples_of_three) print('1', result1) result2 = multiples_of_____.______(multiples_of______) sorted_result2 = list(result2) sorted_result2.sort() print('2', sorted_result2)1 {6} 2 [3, 9]

Key Points

A set stores unsorted unique values.

The set list contains no values.

Sets may contain values of different types.

Sets (Kai)

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

What is a set, and how do I use it?

Objectives

Explain how sets work.

Learn about set operations

A set keeps an unsorted unique collection of things.

- Different from lists

- Lists have a defined order of elements, sets are unordered.

- Lists can contain the same value multiple times, sets do not.

- Sets have a number of fast operations you can use to compare or combine them.

- Sets are great to keep track of things where order an count don’t matter.

- If you put a value that is already in a set into that set again, the set will not change.

beatles = set(['John', 'Paul', 'George', 'Ringo'])

print('Beatles:', beatles)

print('length:', len(beatles))

beatles.add('Ringo')

print('Beatles:', beatles)

print('length:', len(beatles))

Beatles: {'John', 'Ringo', 'Paul', 'George'}

length: 4

Beatles: {'John', 'Ringo', 'Paul', 'George'}

length: 4

Use in to check if something is in a set

Sets allow for efficient check of members.

print('Ringo is one of the Beatles:', 'Ringo' in beatles)

print('Keith is one of the Beatles:', 'Keith' in beatles)

Ringo is one of the Beatles: True

Keith is one of the Beatles: False

You can add values to the set by using add()

beatles.add('Pete')

print('beatles is now:', beatles)

beatles is now: {'Pete', 'John', 'Ringo', 'Paul', 'George'}

You can remove values from the set by using remove()

beatles.remove('Pete')

print('beatles is now:', beatles)